So there’s an article on HN today about how in-app purchase is destroying the game industry. There are a couple of problems with this theory.

The original in-app purchase

See, in the in-app purchase model actually predates phones. It predates video game consoles. It goes all the way back to the arcade, where millions of consumers were happy to pay a whole quarter ($0.89 in 2013 dollars) to pay for just a few minutes. The entire video games industry comes from this model. Kids these days.

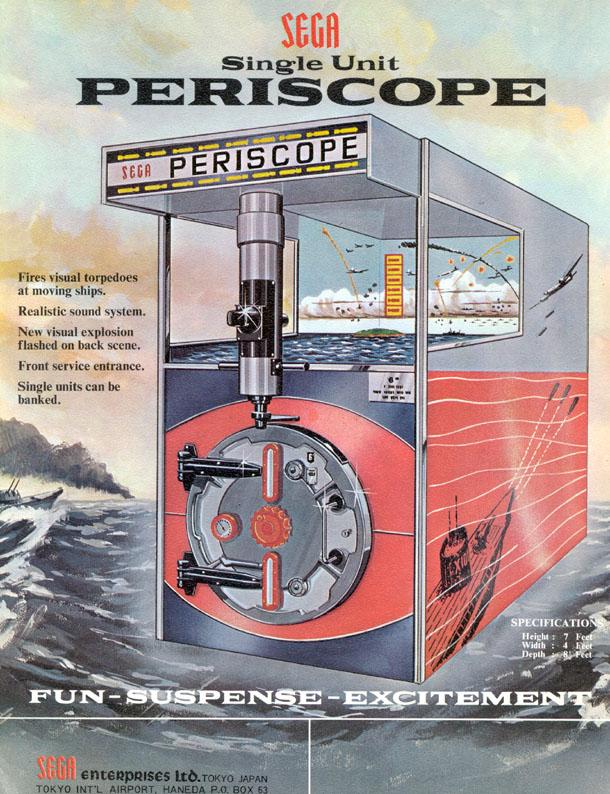

But in fact, the model predates computers. I can trace it at least as far back as the Periscope mechanical arcade game from Sega in 1966 that offers to sell you ten lives for 25 cents ($1.80 in 2013 dollars).

So IAP is not a new model. It is a very old model, the model that started the industry, that everybody forgot about. It’s hard to imagine now, but according to Steve Kent there were some 400,000 arcade street locations in the United States. Compare this with only 121,000 gas stations or 190,000 grocery stores. That is a lot of interest in video gaming under a pay-to-play model.

Examining the pricing pressure of 2014 games

So let’s talk about the sort of world game developers operate in. I’m not one, I lean more towards productivity and enterprise apps in my development. But I sell on the same market, so I know something about it.

The fundamental problem with selling games is that you have 150,000 games that you could play instead. If you think you have a unique game, you probably don’t. And even if you do, it doesn’t matter, because nobody will ever find out–they’ll just play whatever game is in the top list or that their friends saw in the toplist, because nobody is playing any appreciable fraction of 150,000 games.

This is, basically, a problem that is unique to the games market. If you want to take notes on your iPad for example, there are maybe 25 apps that realistically will do what you want. And so you if you are really motivated you can try all those apps for yourself. Or you can look on the internet and find an article where somebody’s done that for you. But nobody’s playing 150,000 games. Not me, not you, not IGN. Nobody. Nobody’s even going to play 1,000 games, which is well under 1% of the games market. And this is why marketing games is very hard. (You’re beginning to discover why I’m not a game developer.)

It’s also unique to mobile. Back in the arcade days, people were limited to playing what games were available in their geographic region. But of course with mobile we have no such constraint; game developers in Pakistan are competing with game developers in the US over the same customers. This is, I think, some of the motivation behind the “apps near me” feature in iOS 7: creating geographic markets where apps can be considered “popular” even if they are not popular in the global market.

In the console wars, there is a similar force that acts to restrict the market: dev kit fees. It generally requires between $2k-$10k to get started developing real console games for consoles, plus yearly fees and profit cuts. After that you have to strike another deal with a licensed publisher, which offers terms on par with any RIAA music label. These forces combine to allow only a thousand or so games for your xbox. That’s still a lot, it’s still much more choice than an ordinary person can rationally consider, but it’s way less than on iOS.

]9 Nintendo even requires you to have a brick-and-mortar office.

People like to reminisce about the glory days of shareware but back then there weren’t 150,000 titles either. DOS games indexes some 600 shareware titles. The Internet Archive indexes some 2,400 items in its “shareware CD collection” that includes such exciting titles as “The Linux Format Magazine Issue 177” and “HP Web Mouse Suite”. Basically, the number of actual shareware games you could realistically run on your computing platform did not number in the thousands.

A new kind of market

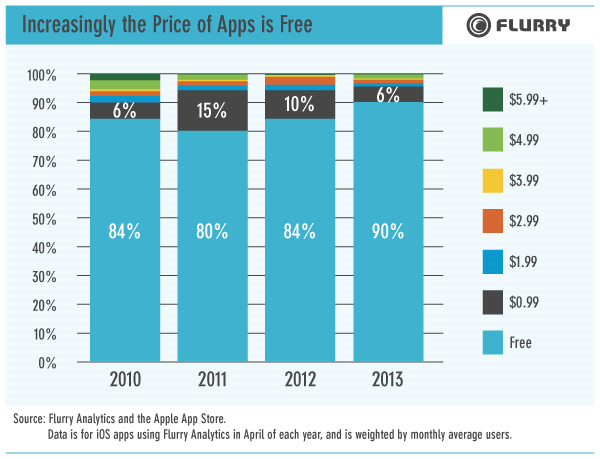

Getting people to play your game in a market of 150,000 alternatives requires a different kind of marketing. For example, if the user can choose to pay $0.99 for your app, or pay zero for another app that’s probably just as fun, they’ll pick the free one. The result follows: 90% of apps are free in 2013 when weighted by monthly average users. And when you look only at those apps that use an experiment/test/data-driven approach for their pricing, you see a strong upward trend in more free apps. So the pricing experiments that these developers are running (you know, actual flipping research, not just speculating baselessly in an HN comment) are telling them it’s better to go free.

Let’s throw some math at the problem. Now I’m just making figures up, but people in the actual game industry don’t like to talk about their own numbers so this is probably as close as we are going to get without a lot more people who make actual money from this opening up their books.

The average revenue per user for a successful game varies widely, but let’s take $1.00 as a benchmark. Most games make most of their revenue during short bursts, say 15 days. If you want to earn enough money, say, to put your $200k development cost in the black in 15 days, that’s about 14k installs per day. Meanwhile there are 5 million downloads per day so that kind of traffic is a tiny, tiny fraction (0.3%) of the daily volume.

Alternatively, say you want to price your game at, I don’t know, $4.99. Now you only have to move 2600 units per day, which sounds a lot easier. However, remember those 5 million downloads? 96% of them are at prices less than $4.99, so the total daily volume in your price bracket is less than 200,000.

In fact, it’s significantly less, because of the top 25 apps of all time, only 60% of them are games. So let’s say that the total games volume above $4.99 is 120k downloads per day. And now you have to move 2.1% of the daily volume in your price bracket each day for 15 days, instead of 0.3%. That is almost a full order of magnitude more by percentage, and it means your marketing team has to reach a much higher number of iOS users than if you only needed to capture 0.3% of the daily volume.

The principle is this: the higher your price is, the less people want to buy it, so you have to raise your price, meaning that even less people want to buy it, and so on. You can pick a price that is high enough to offset the exponential drop in market size, but it is way, way higher than people’s expectations. For example, the console market seems to function at $60/title. You could probably build a mobile games market that functioned at a similar pricepoint.

The trouble is that even software developers, who make their money from selling software, don’t want to spend that much. If you grep the HN comment thread you see all sorts of people who would “gladly spend” $5 or $10 for some game. Very few people are thinking about $40, $60, or $80. That is the kind of pricing it would actually take.

A word on segmentation

Another topic that gets lost in this conversation is market segmentation, or, as software developers tend to know it, “camels and rubber duckies“:

You see, by setting the price at $220, we managed to sell, let’s say, 233 copies of the software, at a total profit of $43,105, which is all good and fine, but something is distracting me: all those people who were all ready to pay more, like those 12 fine souls who would have paid a full $399, and yet, we’re only charging them $220 just like everyone else!

See, the trouble with gamers is that they are non-uniform. Kids in elementary school play games. Your wife in the checkout line plays games. And these people–well, they have vastly different spending power.

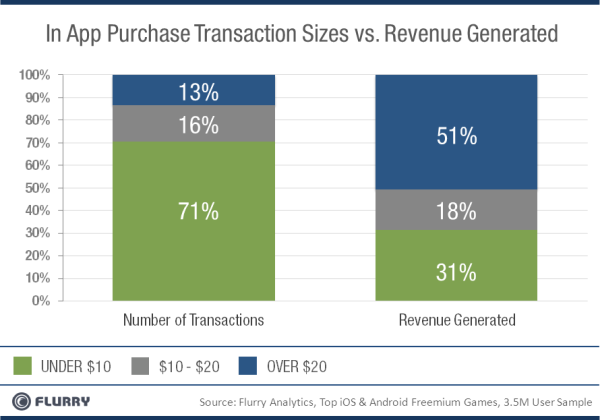

The magic of IAP is it allows a software developer to segment its market; to take in the $.10 in ad spend that the elementary school kid can pay, the $5 that the college student with a side job can pay, and the $100 that the suburban housewife can pay. In fact, something like 51% of all revenue is a transaction over $20:

This means that simply by giving that housewife something to buy, you double your revenue.

Realistic alternatives

If we want to replace IAP, the first order of business is to do some requirements gathering. After all, if we delivered a solution that didn’t meet the requirements, the game developers would look at us funny, and that is exactly the way the conversation between game developers and game customers has gone so far. Step one is to create a solution that meets the requirements. So let’s list them:

- No loss in revenue for game developers

- Ability to segment customers and make more money from richer customers

A console-style market, with console-style gatekeepers and console-style prices, would meet the first requirement, but not the second. Also, developers tend to dislike gatekeepers, so there’s that.

Following the old DOOM and QUAKE model of giving away the first levels and charging for the rest of them might work. The trouble is that when most people think about the “unlocking levels” model they think about charging $1 or $5 for more levels. Meanwhile DOOM charged $40 ($64.49 in 2013 dollars) to unlock the rest of the game. And that was in a market with probably 5 or so competitors, not 150,000. So for this model to work we are talking about $65 upgrade fees, minimum. I would certainly be interested to watch some iOS dev try this model, but I suspect a $65 upsell is quite a lot harder in 2014 than it was in 1993.

Ultimately what I suspect to be true is that you can either have a system with gatekeepers, that limits the supply of games, and $60 up-front cost for a title, or you can have a free-for-all that tries to nickle and dime you.

It may even be possible to have both systems: there is nothing to stop Apple from creating a special, curated section of 100 or so “premium” games that charge console-quality prices. The “Editor’s Choice” and “Featured” lists have some precedent for this. When I say “nothing to stop them”, I mean “other than developer angst about the App Store not being very ‘open'”, which may be significant.

But I doubt it is possible to have the benefits of one system without its inherent drawbacks. When you have 150,000 games competing for the same customers, paid apps aren’t a realistic option unless you have some marketing trick up your sleeve that can overcome a 90% market handicap. The only thing you can do is draw as many customers in as possible and then once you’ve got them in the door bleed them for whatever they can afford, and that’s why we’re here.

Actually there is a third possibility: iOS games could go the way of flash games, where it’s more of a hobby than a viable business. Some 70% of flash game developers are only part-time, whereas only 36% of iOS devs are moonlighters. So there’s a very sobering outcome that we should consider in our analysis: we should consider that there may not be a business model for mobile games that works at all.

You should follow me on Twitter.

Want me to build your app / consult for your company / speak at your event? Good news! I'm an iOS developer for hire.

Like this post? Contribute to the coffee fund so I can write more like it.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Tags

Tags

Jonathan Blow has a talk addressing how in-app purchases affect the quality of games: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxFzf6yIfcc

I appreciate the market pressures you discuss here, but I think part of the problem is that market is so flooded with bad games. Users don’t want to spend money up-front on a game that’s likely to be a dud. Developers know that, so they’re pushed to publish free games and make money via in-app purchases. And, given that model, it’s easier to use psychological tricks to extract purchases from users than it is to craft a genuinely challenging and rewarding game. It’s a vicious cycle.

Consoles avoid this not only by placing a high bar to development, but also by straight-up rejecting games that aren’t up to their quality standards. (Whether they set the right bar is a different discussion, and I’m not qualified to participate). The closest thing on mobile is the “featured” section of the app stores, and the article you linked talks about the poor quality of the selection there, too. As a user, I’ve fallen back to word-of-mouth to learn about worthwhile games; the only one I’ve purchased in recent memory is Super Hexagon, based on a direct recommendation.

Another model developers can use is “pay what you want, above some minimum”, as popularized by Humble Bundle. This addresses customer segmentation to some extent, though of course you’re not reaching actual willingness-to-pay prices.

Neither of these are perfect models, but I think they do offer a way for developers to make a living by producing quality games instead of micropurchase drivel.

$60 to unlock the full game is still a lot less (and still considered reasonable by some) than the $1000-5000 some games reach if you tally up all the IAP content.

Comparing IAP for consumables to arcades is problematic though.

If a coin-op arcade racer offered you to race once for free, then charged 0.50 to race again, or $3 for a faster car as an option for your next race, or $99 for a 70-pack of nitro boosts, that would be a more accurate comparison. Now imagine that your coin-op arcade racer performance is tracked online, and if you spend beyond a certain threshold, you’re shown special content or developer communication because you are now a “whale” and they want to squeeze more cash out of you (standard FTP game industry procedure).

IAP-powered games by large developers are intentionally designed to punish you with long wait times after providing you a deceptively fast-paced and easy first section of the game (known as the “entry funnel”). Most app-reviews don’t get past this point, so the game is described positively in reviews. After that, you are hit with the “infinite money sync” (industry term). There is a level of analytics and intentional hooks into known reward/punishment human-addiction-causing patterns that goes far beyond what any arcade-game developer looked into.

In my opinion, the IAP model that most of these top-grossing games employ really is gross. EA and the like are choosing to damage the industry in exchange for a short-term revenue boost, all at the expense of their players and customers.

Apple and Google should address this, and I like your ideas. They could also simply punish developers utilizing this model by simply adding a “Total spending in this application: $XX” to the bottom of your confirm-your-purchase prompt in the OS.

“Following the old DOOM and QUAKE model of giving away the first levels and charging for the rest of them might work. …So for this model to work we are talking about $65 upgrade fees, minimum.”

You converted all the money amounts, and noted the difference in the competitor pool, but ignored the difference in the number of consumers. The Walking Dead is a game that is operating with a model similar to what you mention, but not charging $65.

I agree that IAP is more similar to the halcyon days of per-quarter arcade gaming than the current console market. I view the console market as being more analogous to the market for books, albums, and movies (home video, not theater). What worries me is that the markets for those media is drastically changing as well.

I’m not worried about the evolution of the pricing model as much as the availability of quality content. I know that I’m happy to pay $60 for a high-quality AAA video game title, but unless there are a lot of people like me, it’s not worth a studio’s resources to put forth a quality title. Moreover, the fewer of me there are, the more homogeneous the product is going to be — because even within the market of people who will pay $60 for a game, there’s a variety of tastes, and so you get titles with mostly mass-market appeal. Once in a while, a studio will put out a critical darling that falls flat, and consequently a studio closes — or gets acquired, or massively restructures…

The problem, I feel is not with IAP and F2P. IAP and F2P are serving a games-consuming market made up of real people. My problem is that I wish people were different. I wish that more people wanted and valued “books” (high quality games for which you pay a larger up-front price) rather than nickel-and-dime experiences. I understand that it’s my problem; one way to ensure failure in the marketplace is to wish that people were different from how they are. I do my own part, however: I don’t let any of my close friends or family spend money on these garbage IAP/F2P titles if I can help it.

I agree with your general assessment—IAP is probably here to say and given that, will surely be abused by the EAs of the world. But for the developer who dislikes such blatant greed and yet still wants to make a living, I believe IAP can offer a perfectly great solution. Something like this:

Give away the game for free on the app stores

Allow people to play a bit for free with no ads or play a lot for free with ads.

Offer a modest upgrade option that makes the game perfectly playable without ads

Maybe even offer an über option that offers extra enhancements and or access which appeals to those who have more to spend.

Each developer will have to take into account their own specific game and how it might be able to make use (or not) of these guidelines, but the general idea is sound: IAP isn’t such a bad thing inherently; it’s just that it is very easily abused by those whose only goal is profit and who are perfectly fine with a severely degraded UX in order to attempt to achieve that goal.

@dwightk Creating more customers you can’t reach doesn’t help you. Having more customers just creates more customers who play the games from the toplists, and that only helps developers in the toplists. It doesn’t create any customers for the 149,000 that are unable to differentiate themselves from each other.

I know that it is purely anecdotal, but how many gamers still rely purely on the top list to find good games? I stopped using the top list on iTunes a long time ago, basically when IAP games migrated from Facebook and took over the list. Now I find most of my games from online mobile gaming sites.

Apps that can’t differentiate themselves from one another will have few, if any, customers, because they are not going to be good. 150,000 games is only possible if most of them are poorly made by inexperienced developers in a short time. Although, with a little organization, a few thousand players could easily test out all of those games and recommend those that were good, and that is what the App Store’s top list is.

But even if half the games on the market were good enough to retain customers (setting aside difficulties in acquiring them), that is not really the problem that IAP is being used to solve, at least not the kind of IAP being criticized.

IAP and coin-op are not the same, despite some similarities. It’s also not sensible to compare the price of coin-op game to a mobile game. That was a different time, with differences in scarcity, physical costs, delivery, and more. It was not possible to reach many users even for the best games. The cost of reaching them was high, the product material costs were high, the availability of skilled developers was highly constrained, the development tools were far inferior, etc. But more to the point, those games were fun and challenging. While we often felt somewhat ripped off by over-hard games, the relationship between what you paid and the reward factor was clear and honest: more play meant better play meant longer play meant cheaper games. Unless you just sucked, and then, oh well, you found another way to have fun. Also, in general, it was much harder to become “addicted” to coin-op games, and they represented a much smaller percentage of personal leisure time, because of their access constraints. There were few, if any, “whales” in coin-op.

Finally, though, the problem with IAP is not the payment model itself. You’re ignoring the meat of the argument in favour of critiquing the semantics.

The problem is that of targeting compulsiveness and using social, difficulty rescaling, and other psychological tricks to give people incentives to play despite the fact that the games are rarely fun, and often not even games by the same standard.

These “games” are only games incidentally. They are more along the lines of behavioural traps disguised as games. While real games certainly can inspire obsessive thinking and compulsive behaviour, that is usually a side-effect of the game being fun. When compulsion is the purpose, and game-ness a side effect, that is a real problem. And it is the mode of IAP, along with virtual currency (coins, gems, what-have-you) which make these no longer proper games of skill with clearly defined challenges and objectives and recognizable win-loss states, but simply perpetual intervention machines which eat vast amounts of time and money.

In-App Purchases are similar to coin-op games, but your entire argument falls apart when one needs to consider someone could play an entire video arcade (or even pinball) game on one single quarter (or whatever it cost) if he/she were skilled enough to keep it going. That was the whole allure of those old games in the first place. They were games of skill. When Roger Sharpe testified before a committee in Manhattan over legalization of pinball in NYC in the late 1970’s the fact they were games of skill was his major defense for pinball. They were made illegal decades earlier because they were seen as gambling machines.

With most practices involving in-app purchases with games on iOS this doesn’t apply. In the old days you paid one quarter for a set amount of lives and allowed to play the full extent of the game until you failed. You didn’t pay a quarter to unlock some aspect of the game. You didn’t keep feeding a pinball machine more money to get a multiball. You didn’t feed more money into a video arcade game to cheat or to unlock a weapon you couldn’t get otherwise. In-app purchases themselves didn’t cheapen video games. It’s the ways they’re used to push games away from games of skill into the realm of moneypit rigged gambling devices that does.

You have given a beautiful analysis of revenue models, but missed the entire point of the other article.

It argues that IAP have reduced mobile gaming to nothing more than skinner boxes, dragging cash out of users to the detriment of the game experience.

I was in the industry for 12 years and our guiding purpose was always “is this fun?” I’ve been out for a couple of years but went back to talk to some friends about a job and the focus was entirely about “how can we monetize our users”.

Games are entertainment. The industry has lost sight of that. Your article treats it as just the same as a utility: just profit and loss. I’d like to think it can still offer more than that.

I would argue that “No loss in revenue for game developers” isn’t actually a requirement, and in fact is what is driving these outrageous IAPs.

You simply can’t have 150,000 competitors in the game space, each earning as much as Carmack did. They could get those salaries because their games were all new and unique (mostly by skill, but partially also because the field was so young). There just isn’t that much (legitimate) money in the game industry for little one-off derivative games. The value isn’t there.

Furthermore, this situation is not unique to games. How much did you pay this decade for email clients? For web browsers, or operating systems? Or spell checkers, or file managers? All of these things have come way down in price, as everything becomes integrated and automatic and included with the core system.

So why is the (non-game) software field booming today? Because it’s getting into new areas. People don’t seem to have any trouble paying $30 for games that are truly new and unique, like Minecraft or Kerbal Space Program. These are the Carmacks of today, and they’re earning it.

There are different types of IAP, some good, some bad. I wouldn’t argue that there are lots of potential good uses for IAP. Take League of Legends or Team Fortress 2, for example. Both manage to make money (I think even a large amount) without resorting to psychological exploitation (or even imbalancing multiplayer.) Games like dungeon keeper, on the other hand, get you hooked on a game mechanic (like building a room) and then get you to pay to speed up the process as you progress. It just feels like you end up paying 2014 AAA-game prices *even if in installments) to get 1994 shareware games… on an ipad.

I think that if that trend continues, “game” making will become more about maximizing short term profit regardless of the quality of the games. So in that sense, the industry is cannibalizing itself. The industry will still exist, but it won’t look anything like the one of the last 20 years.

My hunch is the “freemium is bad” argument is primarily an oversimplification of the underlying concern — the erosion of trust and how that manifests during gameplay.

When I play a traditional “pay” game, I trust that the developer want me to finish the entire game. After all, the team slaved away creating all that content and the player should damn well appreciate their effort.

As a result, when I get stuck at some point in a game (Dead Space 2 being a recent example), I trust that there’s a way forward and with a little more effort or practice, or perhaps if I retrace my steps, I’ll become unstuck and move along the path toward completion.

Because the developer and I are working with a common goal in mind — get Eric to the end of the game — I am confident that at any point in the game I will be capable of completing the challenges set forth (no matter how stingy the Dead Space guys are with ammo).

With freemium games, that trust is obliterated. When I can’t progress, I am forced to ask a fun-sucking question — is the developer trying to extort money from me in order to continue? Am I unable to continue because I just haven’t mastered some in-game skill or is this simply the point at which I’m supposed to hand over my tithe?

Candy Crush is an obvious (if extreme) example. When you can’t complete a level after the 20th try, the player begins to feel that the developer is expressly barring their passage. And at that point, the game ceases to be fun, at least for the generations of gamers who saved the princess.

You mentioned DOOM and Quake and I was happy back in the day to pay for more levels. Now imagine getting all the levels for free, but every two or three levels you have trouble progressing. Is this because you haven’t developed enough skills to complete the level or is it because you have to pay a buck or two to have your character buffed to continue. Hell, just TELL me that I have to pay in order to progress. But by making it a constant implicit question, you just alienate a heck of a lot of traditional gamers.

@Luc: Your comment “Games are entertainment. The industry has lost sight of that.” encapsulates the core friction around F2P. The games business is a business. Yes, the product is entertainment but in the end only those products which are financially successful enable the makers to make more. Niche appeal is often the worst business situation. Users love the games but, to the author’s point, won’t pay enough to keep the company in business.

The industry hasn’t lost site of anything. It is an industry. Industries operate on profit and loss. Would you argue that a bank prioritize art over commerce? Its shareholders would disagree with you. Yet you think nothing of demanding that of a gaming business. It isn’t realistic.

Game hobbyists are free to pursue gaming as an art. Companies are not.

Something that I am missing here is also the

‘pay what you want’ approach of the Humble Bundle.

As you pointed out, the customer base is not uniform and the spending power and willingness is fastly different.

Assuming, you manage to trigger their spending willingness (cause your game is good), this willingness transferes into an individual amount of value, which related to the spending power.

A elementary school kid this could transfere to like 10% of his monthly budget, while for a working person it might be 1% of his daily budget, but then the daily budget of a working person is absolut, the 1% is only 0.10$ but the 1% is actually 10 Bucks.

You could try to incorporate that into your ‘pay for your next level’ but I haven’t seen it yet in a good way.

So far the only way, is that the more you spent the bigger your discount is (for certain IAP) but IMHO it discourages me to spent money rather than spending it because, the 1$ is not worth it if you look at the 100$ purchase but I dont want to spend a 100$. So there I go and buy nothing.

@Drew

I think the number of people who might buy a game like The Walking Dead is probably bigger than the number of people who would have bought Doom or Quake back in the day.

Maybe that is only possible when it is tied to some other entity which is providing advertising (an AMC show), but I hope that there are enough people out there that ~6 $10 upgrades could replace the 1 $65 upgrade.